¶

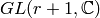

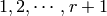

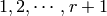

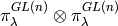

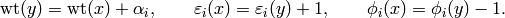

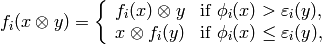

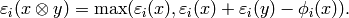

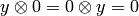

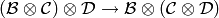

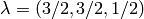

¶Let  be a partition. The Young diagram of

be a partition. The Young diagram of  is the

array of boxes having

is the

array of boxes having  boxes in the

boxes in the  -th row, left adjusted. Thus

if

-th row, left adjusted. Thus

if  the diagram is:

the diagram is:

![\def\lr#1#2#3{\multicolumn{1}{#1@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}#2}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#3$}}}\raisebox{-6ex}{\begin{array}[b]{cccc}\cline{1-3}\lr{|}{|}{\;}&\lr{|}{|}{\;}&\lr{|}{|}{\;}\\ \cline{1-3}\lr{|}{|}{}&\lr{|}{|}{}&&\\ \cline{1-2}\end{array}}](_images/math/8888b2384babdfd89404d364d2c65a5cd0f9907c.png)

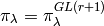

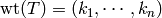

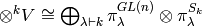

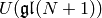

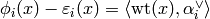

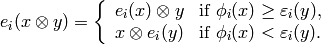

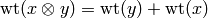

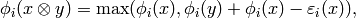

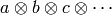

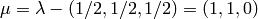

A semi-standard Young tableau of shape  is a filling of the

box by integers in which the rows are weakly decreasing and the columns are

strictly decreasing. Thus

is a filling of the

box by integers in which the rows are weakly decreasing and the columns are

strictly decreasing. Thus

![\def\lr#1#2#3{\multicolumn{1}{#1@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}#2}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#3$}}}\raisebox{-6ex}{\begin{array}[b]{cccc}\cline{1-3}\lr{|}{|}{3}&\lr{|}{|}{2}&\lr{|}{|}{2}\\ \cline{1-3}\lr{|}{|}{2}&\lr{|}{|}{1}&&\\ \cline{1-2}\end{array}}](_images/math/b16fc8dcb8f20b794e615033a6e6b89c7c53254d.png)

is a semistandard Young tableau. Sage has a Tableau class, and you may create this tableau as follows:

sage: T=Tableau([[3,2,2],[2,1]]); T

[[3, 2, 2], [2, 1]]

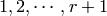

A partition of length  is a dominant weight for

is a dominant weight for  according

to the description of the ambient space in Standard realizations of the ambient spaces. Therefore

it corresponds to an irreducible representation

according

to the description of the ambient space in Standard realizations of the ambient spaces. Therefore

it corresponds to an irreducible representation

of

of  .

.

It is true that not every dominant weight  is a partition, since a

dominant weight might have some values

is a partition, since a

dominant weight might have some values  negative. The dominant

weight

negative. The dominant

weight  is a partition if and only if the character of

is a partition if and only if the character of  is a polynomial as a function on the space

is a polynomial as a function on the space  .

Thus for example

.

Thus for example  with

with  ,

which is a dominant weight but not a partition, and the character is not

a polynomial function on

,

which is a dominant weight but not a partition, and the character is not

a polynomial function on

Theorem (Littlewood) If  is a partition, then the number of Semi-Standard Young

Tableaux with shape

is a partition, then the number of Semi-Standard Young

Tableaux with shape  and entries in

and entries in  is the dimension

of

is the dimension

of  .

.

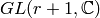

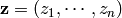

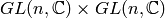

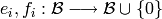

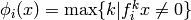

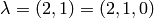

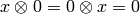

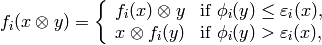

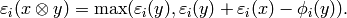

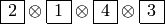

For example, if  and

and  , then we find 15 tableaux with shape

, then we find 15 tableaux with shape  and entries in

and entries in  :

:

![\begin{array}{ccccc}{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{1}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}\\\\{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{1}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}\\\\{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{1}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{1}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}&{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}&\lr{2}&\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{3}&\lr{3}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\end{array}$}}\end{array}](_images/math/f0d9d736f947c185d9640cbf94b514c4f4aadc82.png)

This is consistent with the theorem since the dimension of the irreducible

representation of  with highest weight

with highest weight  has dimension 15:

has dimension 15:

sage: A2=WeylCharacterRing("A2")

sage: A2(3,2,0).degree()

15

In fact we may obtain the character of the representation from the set of tableaux.

Indeed, one of the definitions of the Schur polynomial (due to Littlewood) is

the following combinatorial one. If  is a tableaux, define the

weight of

is a tableaux, define the

weight of  to be

to be  where

where

is the number of

is the number of  ‘s in the tableaux. Then the

multiplicity of

‘s in the tableaux. Then the

multiplicity of  in the character

in the character  is the

number of tableaux of weight

is the

number of tableaux of weight  . Thus if

. Thus if

, we have

, we have

where the sum is over all semistandard Young tableaux of shape  that have entries in

that have entries in  .

.

¶

¶Representations of the symmetric group  are parametrized by partitions

are parametrized by partitions

of

of  . The parametrization may be characterized as follows.

Let

. The parametrization may be characterized as follows.

Let  be any integer

be any integer  . Then both

. Then both  and

and  act on

act on  where

where  . Indeed,

. Indeed,  acts on

each

acts on

each  and

and  permutes them. Then if

permutes them. Then if  is the

representation of

is the

representation of  with highest weight vector

with highest weight vector  and

and  is the irreducible representation of

is the irreducible representation of  parametrized by

parametrized by  then

then

as bimodules for the two groups. This is Frobenius-Schur duality and

it serves to characterize the parametrization of the irreducible

representations of  by partitions of

by partitions of  .

.

Let us say that a Tableaux  of shape

of shape  is standard

if

is standard

if  contains each entry

contains each entry  exactly once.

exactly once.

Theorem (Young, 1927) The degree of  is the number of standard

tableaux of shape

is the number of standard

tableaux of shape  .

.

References:

The Robinson-Schensted-Knuth correspondence gives bijections between pairs of tableaux of various types and combinatorial objects of different types. We will not review the correspondence in detail here, but see the references. We note that Schensted insertion is implemented as the method schensted_insertion() of Tableau class in Sage.

Thus we have the following bijections:

as

as  runs through the partitions of

runs through the partitions of  are in bijection

with the

are in bijection

with the  elements of

elements of  .

. and

and  of shape

of shape  where

where

runs through the partitions of

runs through the partitions of  such that

such that  is a standard tableau and

is a standard tableau and  is a semistandard tableau in

is a semistandard tableau in

are in bijection with the

are in bijection with the  words of

length

words of

length  in

in  .

. and

and  of the same shape

of the same shape  but

arbitrary size in

but

arbitrary size in  are in bijection with

are in bijection with  positive integer matrices.

positive integer matrices. and

and  of conjugate shapes

of conjugate shapes

and

and  are in bijection with

are in bijection with  matrices with entries

matrices with entries  or

or  .

.The three bijections cited above have the following analogs in representation theory.

is an

is an  bimodule

with of dimension

bimodule

with of dimension  . It decomposes as a direct sum of

. It decomposes as a direct sum of

.

. -dimensional vector space

-dimensional vector space  where

where  into the direct sum of

into the direct sum of  as a bimodule, where

as a bimodule, where  runs through partitions of

runs through partitions of  .

. on which

on which  acts by

acts by  . The polynomial ring

decomposes into the direct sum of

. The polynomial ring

decomposes into the direct sum of  .

Taking traces gives the Cauchy identity.

.

Taking traces gives the Cauchy identity. . Taking traces gives the dual

Cauchy identity.

. Taking traces gives the dual

Cauchy identity.The theory of quantum groups interpolates between the representation

theoretic picture and the combinatorial picture, and thereby

explains these analogies. The representation  is reinterpreted as a module for the quantized enveloping algebra

is reinterpreted as a module for the quantized enveloping algebra

, and the representation

, and the representation

is reinterpreted as a module for the Iwahori

Hecke algebra. Then Frobenius-Schur duality persists. Reference:

is reinterpreted as a module for the Iwahori

Hecke algebra. Then Frobenius-Schur duality persists. Reference:

-analogue of

-analogue of  , Hecke algebra,

and the Yang-Baxter equation. Lett. Math. Phys. 11 (1986), no. 3, 247–252.

, Hecke algebra,

and the Yang-Baxter equation. Lett. Math. Phys. 11 (1986), no. 3, 247–252.When  , we recover the representation story. When

, we recover the representation story. When  ,

we recover the combinatorial story.

,

we recover the combinatorial story.

References:

-analogue of classical Lie algebras. J. Algebra 165 (1994), no. 2,

295–345.

-analogue of classical Lie algebras. J. Algebra 165 (1994), no. 2,

295–345.Kashiwara considered the highest weight modules of quantized enveloping

algebras  in the limit when

in the limit when  . The enveloping

algebra cannot be defined when

. The enveloping

algebra cannot be defined when  , but a limiting structure can still be

detected. This is the crystal basis of the module.

, but a limiting structure can still be

detected. This is the crystal basis of the module.

Kashiwara’s crystal bases have a combinatorial structure that sheds light even on purely combinatorial constructions on tableaux that predated quantum groups. It gives a good generalization to other Cartan types.

We will not make the most general definition of a crystal. See the references

for a more general definition. Let  be the weight lattice of a classical

Cartan type.

be the weight lattice of a classical

Cartan type.

We now define a crystal of type  . Let

. Let  be a set,

and let

be a set,

and let  be an auxiliary element. For each index

be an auxiliary element. For each index  we assume there given maps

we assume there given maps  , maps

, maps  and a map

and a map

satisfying certain

assumptions, which we now describe.

It is assumed that if

satisfying certain

assumptions, which we now describe.

It is assumed that if  then

then  if and only if

if and only if  . In this case, it

is assumed that

. In this case, it

is assumed that

Moreover, we assume that

for all  .

.

Assumption (Regularity) We will assume that  is the

number of times that

is the

number of times that  may applied to

may applied to  , and that

, and that  is the

number of times that

is the

number of times that  may be applied. That is,

may be applied. That is,

and

and

This regularity assumption is not made by Kashiwara, but it is satisfied by the

crystals that we are concerned with here. Kashiwara also allows  and

and  to take the value

to take the value  .

.

Given the crystal  , the character

, the character  is:

is:

.

.

Given any highest weight  , constructions of Kashiwara and Nakashima,

Littelmann and others produce a crystal

, constructions of Kashiwara and Nakashima,

Littelmann and others produce a crystal  such that

such that

, where

, where  is the irreducible

character with highest weight

is the irreducible

character with highest weight  , as in Representations and Characters.

, as in Representations and Characters.

The crystal  is not uniquely characterized by the

properties that we have stated so far. For Cartan types A,D,E it may

be characterized by these properties together with certain other

Stembridge axioms. We will take it for granted that there is a

unique “correct” crystal

is not uniquely characterized by the

properties that we have stated so far. For Cartan types A,D,E it may

be characterized by these properties together with certain other

Stembridge axioms. We will take it for granted that there is a

unique “correct” crystal  and discuss how these

are constructed in Sage.

and discuss how these

are constructed in Sage.

Before giving examples of crystals, we digress to help you install dot2tex, which you will need in order to make latex images of crystals.

You may download the following file:

http://sage.math.washington.edu/home/nthiery/dot2tex-2.8.7.spkg

Then run:

sage -i dot2tex-2.8.7.spkg

to install the package.

For type  , Kashiwara and Nakashima put a crystal

structure on the set of tableaux with shape

, Kashiwara and Nakashima put a crystal

structure on the set of tableaux with shape  in

in  , and this is a realization of

, and this is a realization of

. Moreover, this construction extends

to other Cartan types, as we will explain. At the moment, we will

consider how to draw pictures of these crystals.

. Moreover, this construction extends

to other Cartan types, as we will explain. At the moment, we will

consider how to draw pictures of these crystals.

Once you have dot2tex installed, you may make images pictures of crystals as follows:

sage: C=CrystalOfTableaux("A2",shape=[2,1])

sage: C.latex_file("/tmp/a2rho.tex")

Here  . The crystal C is

. The crystal C is  .

The character

.

The character  will therefore be the eight-dimensional irreducible

character with this highest weight. The method latex_file() produces

will therefore be the eight-dimensional irreducible

character with this highest weight. The method latex_file() produces

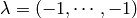

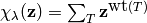

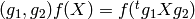

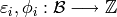

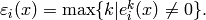

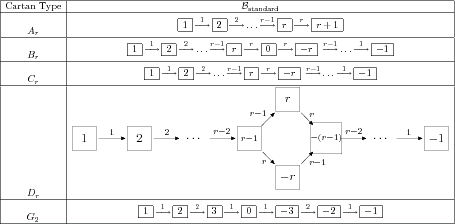

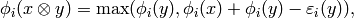

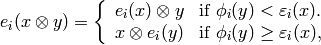

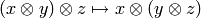

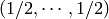

As you can see, the elements of this crystal are exactly the eight tableaux

of shape  with entries in

with entries in  . The convention is that if

. The convention is that if

and

and  , or equivalently

, or equivalently  , then we

draw an arrow from

, then we

draw an arrow from  . Thus the highest weight tableau is the

one with no incoming arrows. Indeed, this is:

. Thus the highest weight tableau is the

one with no incoming arrows. Indeed, this is:

![{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\lr{1}&\lr{1}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\end{array}$}}](_images/math/e1c44d83cf8259bfecf9b8196308399679273f03.png)

We recall that the weight of the tableau is  where

where  is the number of

is the number of

‘s in the tableau, so this tableau has weight

‘s in the tableau, so this tableau has weight  , which indeed equals

, which indeed equals  .

.

Once the crystal is created, you have access to the ambient space and its methods through the method :meth:weight_lattice_realization():

sage: L = C.weight_lattice_realization(); L

Ambient space of the Root system of type ['A', 2]

sage: L.fundamental_weights()

Finite family {1: (1, 0, 0), 2: (1, 1, 0)}

The highest weight vector is available as follows:

sage: v = C.highest_weight_vector(); v

[[1, 1], [2]]

or more simply:

sage: C[0]

[[1, 1], [2]]

Now we may apply the operators  and

and  to

move around in the crystal:

to

move around in the crystal:

sage: v.f(1)

[[1, 2], [2]]

sage: v.f(1).f(1)

sage: v.f(1).f(1) == None

True

sage: v.f(1).f(2)

[[1, 3], [2]]

sage: v.f(1).f(2).f(2)

[[1, 3], [3]]

sage: v.f(1).f(2).f(2).f(1)

[[2, 3], [3]]

sage: v.f(1).f(2).f(2).f(1) == v.f(2).f(1).f(1).f(2)

True

You can construct the character if you first make a Weyl character ring:

sage: A2 = WeylCharacterRing("A2")

sage: C.character(A2)

A2(2,1,0)

For each of the classical Cartan types there is a standard

crystal  from which other

crystals can be built up by taking tensor products and extracting

constituent irreducible crystals. This procedure is sufficient

for Cartan types

from which other

crystals can be built up by taking tensor products and extracting

constituent irreducible crystals. This procedure is sufficient

for Cartan types  and

and  . For types

. For types  and

and  the standard crystal must be supplemented with a spin crystal.

the standard crystal must be supplemented with a spin crystal.

The crystal of letters is a special case of the crystal of tableaux

in the sense that  is isomorphic

the crystal of tableaux whose highest weight

is isomorphic

the crystal of tableaux whose highest weight  is the

highest weight vector of the standard representation. Thus compare:

is the

highest weight vector of the standard representation. Thus compare:

sage: CrystalOfLetters("A3")

The crystal of letters for type ['A', 3]

sage: CrystalOfTableaux("A3",shape=[1])

The crystal of tableaux of type ['A', 3] and shape(s) [[1]]

These two crystals are different in implementation, but they are isomorphic, and in fact the second crystal is constructed from the first. Crystals of letters have a special role in the theory since they are particularly simple, yet as Kashiwara and Nakashima showed, the crystals of tableaux can be created from them. We will review how this works.

Kashiwara defined the tensor product of crystals in a purely combinatorial

way. The beauty of this construction is that it exactly parallels the

tensor product of crystals of representations. That is, if

and

and  are dominant weights, then

are dominant weights, then

is a (usually

disconnected) crystal which may contain multiple copies of

is a (usually

disconnected) crystal which may contain multiple copies of

(for another dominant weight

(for another dominant weight  ) but the

number of copies of

) but the

number of copies of  is exactly the multiplicity

of

is exactly the multiplicity

of  in

in  .

.

We will describe two conventions for the tensor product of crystals. These conventions would have to be modified slightly without the regularity assumption.

As a set, the tensor product  of crystals

of crystals

and

and  is the Cartesian product, but we denote the

ordered pair

is the Cartesian product, but we denote the

ordered pair  with

with  and

and  by

by  . We define

. We define  . We define

. We define

and

It is understood that  . We also define:

. We also define:

As a set, the tensor product  of crystals

of crystals

and

and  is the Cartesian product, but we denote the

ordered pair

is the Cartesian product, but we denote the

ordered pair  with

with  and

and  by

by  . We define

. We define  . We define

. We define

and

It is understood that  . We also define

. We also define

The tensor product is associative:  is

an isomorphism

is

an isomorphism  ,

and so we may consider tensor products of arbitrary numbers of crystals.

,

and so we may consider tensor products of arbitrary numbers of crystals.

The relationship between the two definitions is simply that the

Kashiwara tensor product  is the

alternate tensor product

is the

alternate tensor product  in

reverse order. Sage uses the alternative tensor product. Even

though the tensor product construction is a priori asymmetrical,

both constructions produce isomorphic crystals, and in particular Sage’s

crystals of tableaux are identical to Kashiwara’s.

in

reverse order. Sage uses the alternative tensor product. Even

though the tensor product construction is a priori asymmetrical,

both constructions produce isomorphic crystals, and in particular Sage’s

crystals of tableaux are identical to Kashiwara’s.

You may construct the tensor product of several crystals in Sage using TensorProductOfCrystals:

sage: C = CrystalOfLetters("A2")

sage: T = TensorProductOfCrystals(C,C,C); T

Full tensor product of the crystals [The crystal of letters for type ['A', 2],

The crystal of letters for type ['A', 2], The crystal of letters for type ['A', 2]]

sage: T.cardinality()

27

sage: T.highest_weight_vectors()

[[1, 1, 1], [1, 2, 1], [2, 1, 1], [3, 2, 1]]

This crystal has four highest weight vectors. We may understand this as follows:

sage: A2 = WeylCharacterRing("A2")

sage: chi_C = C.character(A2)

sage: chi_T = T.character(A2)

sage: chi_C

A2(1,0,0)

sage: chi_T

A2(1,1,1) + 2*A2(2,1,0) + A2(3,0,0)

sage: chi_T == chi_C^3

True

As expected, the character of T is the cube of the character of C, and

representations with highest weight  ,

,  and

and  . This

decomposition is predicted by Frobenius-Schur duality: the multiplicity

of

. This

decomposition is predicted by Frobenius-Schur duality: the multiplicity

of  in

in  is the degree of

of

is the degree of

of  .

.

It is useful to be able to select one irreducible constitutent of T. If we only want one of the irreducible constituents of T, we can specify a list of highest weight vectors by the option generators. If the list has only one element, then we get an irreducible crystal. We can make four such crystals:

sage: [T1,T2,T3,T4] = \

[TensorProductOfCrystals(C,C,C,generators=[v]) for v in T.highest_weight_vectors()]

sage: [B.cardinality() for B in [T1,T2,T3,T4]]

[10, 8, 8, 1]

sage: [B.character(A2) for B in [T1,T2,T3,T4]]

[A2(3,0,0), A2(2,1,0), A2(2,1,0), A2(1,1,1)]

We see that two of these crystals are isomorphic, with character A2(2,1,0). Try:

sage: T1.plot(), T2.plot(), T3.plot(), T4.plot()

Elements of TensorProductOfCrystals(A,B,C, ...) are represented by

sequences [a,b,c, ...] with a in A, b in B, etc.

This of course represents  .

.

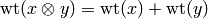

Sage implements the CrystalOfTableaux as a subcrystal of a tensor product of the CrystalOfLetters. You can see how its done as follows:

sage: T = CrystalOfTableaux("A3",shape=[3,1])

sage: v = T.highest_weight_vector().f(1).f(2).f(3).f(1).f(2); v

[[1, 3, 4], [2]]

sage: v._list

[2, 1, 3, 4]

We’ve looked at the internal representation of  , where it is represented

as an element of the fourth tensor power of the CrystalOfLetters. We see that

the tableau:

, where it is represented

as an element of the fourth tensor power of the CrystalOfLetters. We see that

the tableau:

![{\def\lr#1{\multicolumn{1}{|@{\hspace{.6ex}}c@{\hspace{.6ex}}|}{\raisebox{-.3ex}{$#1$}}}\raisebox{-.6ex}{$\begin{array}[b]{ccc}\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{1}&\lr{3}&\lr{4}\\\cline{1-1}\cline{2-2}\cline{3-3}\lr{2}\\\cline{1-1}\end{array}$}}](_images/math/1536687e4bafcabfcf47aec38b21f8db9983ba15.png)

is interpreted as the tensor:

The elements of the tableau are read from bottom to top and from left to right. This is the inverse middle-Eastern reading of the tableau. See Hong and Kang, loc. cit. for discussion of the readings of a tableau.

For the Cartan types  ,

,  or

or  , CrystalOfTableaux are capable of making any

finite crystal. (For type

, CrystalOfTableaux are capable of making any

finite crystal. (For type  it is necessary that the highest weight

it is necessary that the highest weight  be

a partition.)

be

a partition.)

For Cartan types  and

and  , CrystalOfTableaux fail to make

, CrystalOfTableaux fail to make  if

if  is half-integral. For type

is half-integral. For type  you can do this:

you can do this:

sage: B = FastCrystal(['B',2],shape=[3/2,1/2]); B

The fast crystal for B2 with shape [3/2,1/2]

sage: v = B.highest_weight_vector(); v.weight()

(3/2, 1/2)

However FastCrystals are only available for rank two Cartan types. We therefore have to do something else to create crystals of half-integral weight.

For types  and

and  the solution to this problem involves the use of

spin crystals.

the solution to this problem involves the use of

spin crystals.

The spin crystal has highest weight  . This is

the last fundamental weight. The irreducible representation with this weight

is the spin representation of degree

. This is

the last fundamental weight. The irreducible representation with this weight

is the spin representation of degree  . Its crystal is hand-coded in

Sage:

. Its crystal is hand-coded in

Sage:

sage: Cspin = CrystalOfSpins("B3"); Cspin

The crystal of spins for type ['B', 3]

sage: Cspin.cardinality()

8

We can make use of this to construct an arbitrary crystal with

highest weight  , where

, where  is a half-integral

weight. For example, suppose that

is a half-integral

weight. For example, suppose that  . The

corresponding irreducible character will have degree 112:

. The

corresponding irreducible character will have degree 112:

sage: B3=WeylCharacterRing("B3")

sage: B3(3/2,3/2,1/2).degree()

112

So  will have 112 elements. We can

find it as a subcrystal of Cspin

will have 112 elements. We can

find it as a subcrystal of Cspin ,

where

,

where  :

:

sage: B3(1,1,0)*B3(1/2,1/2,1/2)

B3(1/2,1/2,1/2) + B3(3/2,1/2,1/2) + B3(3/2,3/2,1/2)

We see that just taking the tensor product of these two crystals will produce a reducible crystal with three constitutents, and we want to extract the one we want. We do that as follows:

sage: C1 = CrystalOfTableaux("B3",shape=[1,1])

sage: C = TensorProductOfCrystals(C1,Cspin,generators=[[C1[0],Cspin[0]]])

sage: C.cardinality()

112

This is the desired crystal.

A similar situation pertains for type  , but now there are two spin crystals,

both of degree

, but now there are two spin crystals,

both of degree  . These are hand-coded in sage:

. These are hand-coded in sage:

sage: SpinPlus = CrystalOfSpinsPlus("D4")

sage: SpinMinus = CrystalOfSpinsMinus("D4")

sage: SpinPlus[0].weight()

(1/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2)

sage: SpinMinus[0].weight()

(1/2, 1/2, 1/2, -1/2)

sage: [C.cardinality() for C in [SpinPlus,SpinMinus]]

[8, 8]

You can use them similarly to the type B crystal of spins in order to construct any crystal of half-integral weight.

Let  be a Lie group and

be a Lie group and  a Levi subgroup. We have already seen

that the Dynkin diagram of

a Levi subgroup. We have already seen

that the Dynkin diagram of  is obtained from that of

is obtained from that of  by erasing

one or more nodes.

by erasing

one or more nodes.

If  is a crystal for

is a crystal for  , then we may obtain the corresponding

crystal for

, then we may obtain the corresponding

crystal for  by a similar process. For example if the Dynkin-diagram

for

by a similar process. For example if the Dynkin-diagram

for  is obtained from the Dynkin diagram for

is obtained from the Dynkin diagram for  by erasing the

by erasing the  -th

node, then if we erase all the edges in the crystal

-th

node, then if we erase all the edges in the crystal  that

are labeled with

that

are labeled with  , we obtain a crystal for

, we obtain a crystal for  .

.

Sage contains support for affine crystals. These lie outside the scope of this document.